Why do smart kids make foolish choices?

Short of locking up adolescents until they mature into responsible adults, both parents and educators wrestle with how to keep them safe from harmful behaviors. The risk list is long: from smoking, drinking, and using hard drugs, to driving too fast, having unprotected sex, and so on. They know better. We know they know better. But many still get into trouble.

Project ALERT’s Andrea Warren sat down with behavioral psychologist Laurence Steinberg, PhD, whose specialty is the adolescent brain, for a Q&A session to find out why.

Can new studies on the brain help us understand why teens take risks?

Yes. In the past dozen years, because of increasingly sophisticated imaging technology such as MRI, we have learned a great deal about brain development. We now know that the brain changes more dramatically in adolescence than at any other time in the human lifecycle, with the exception of our first three years of life. We’ve all suspected it, but now we know that teens’ brains, and particularly young teens’ brains, are different. What we’re learning about how they make decisions can assist us in developing more effective strategies and interventions to address adolescents and risky behavior.

So why do teenagers take foolish risks?

The answer is complex, but in simple terms, because it feels good and they often can’t help themselves. Two key systems of the brain are responsible. The first controls our responses to rewarding experiences and the processing of emotion. The second controls rational, logical thinking and self control. But these two parts don’t mature on the same timetable. Early in adolescence, there is a significant increase in the arousal of the first system, which increases individuals’ sensitivity to rewards. The maturation of the system that governs self-control is much more gradual, and is not complete until the mid-twenties. Middle adolescence is a time of heightened reward-seeking, but still immature impulse control. That’s why sensation-seeking is so intense at this time.

But why do teens, and particularly young teens, have these feelings in such extremes?

Because of a brain chemical called dopamine. There is more dopamine activity in young teens than at any other time of life. It’s responsible for feelings of pleasure. Because of it, teens want to go higher and faster. They have intense crushes and are full of passions and longings. Everything is heightened in intensity. It drives them to seek out thrills and all kinds of experiences that feel good. At the same time, because their logical thinking processes haven’t kept up, they aren’t considering consequences. It’s why a teenager can get straight A’s, yet experiment with drugs or get into a fight. Teens take risks because they are not yet fully able to put on the brakes and because risk feels good. This goes on until self-control matures.

You’ve been involved in imaging studies related to peer pressure. What have you learned that we didn’t know before?

We’ve always known that teens engage in more risky behavior when they are with their friends. Most adults can recall this about themselves as teens. Statistics prove that teens riding in cars together have higher accident rates. Yet they can be good drivers when they’re alone or there’s an adult in the car. My research team and I decided to see if teen drivers take more risks if they know their friends are watching them, even if they can’t see the friends. In our study we had young adults, college students, and teens from 14 to 18 come to our lab, bringing several friends with them. Each of our subjects played a six-minute video driving game while we imaged their brains. We offered them rewards for driving the farthest in the six minutes. They had to make decisions such as stopping at yellow lights, which delayed them, or racing through them, even though that meant a higher risk of an accident and major delays. Each participant played the game four times, twice alone and twice with their friends watching them from the next room. Participants knew the friends were there but could not see or hear them.

And what happened?

With the college students and young adults there was no meaningful difference in risk taking when their friends were watching. But when the young teens knew their friends were watching, they ran 40 percent more yellow lights and had 60 percent more crashes. The presence of their peers activated the reward circuitry in their brains, overwhelming any warning signals about danger. We often think of peer pressure as kids coercing each other into doing things they know they shouldn’t, but this is telling us that all it takes is the knowledge that their friends are watching and they’ll take risks. It reinforces why really good kids will do really dumb things if their friends are around.

You’ve also introduced this brain research into the field of juvenile justice and were the lead scientist in a brief filed by the American Psychological Association in the case in which the US Supreme Court abolished the death penalty for juveniles. You have also argued that some adolescent criminals shouldn’t be given life in prison without parole.

What I have said regarding teen criminals is that because of their youth, they are less responsible for their behavior than adults. As a result, it is possible that they should be treated differently. I feel they should be punished, but also that brain maturity should be considered, and that this should be done on a case by case basis. Because young criminals are likely to change as their brains mature, perhaps we should then revisit each case to see what the individual is now like.

One bad decision some kids make is experimenting with drugs. Are teens more susceptible to problems with drugs than adults?

We have growing evidence that the brain is much more vulnerable to substance abuse in young teens. Some excellent studies have been done with other mammals, whose brains are similar to ours, showing that when young and old mammals—in this case, mice--are exposed to the same doses of alcohol or other substances, young mammals are much more likely to become addicted. This is a very serious problem. Study after study shows that nicotine is as addictive as heroin or cocaine. Teens who drink and drive take foolish risks. The marijuana being sold today is much more powerful than what was available when we were teens, making users susceptible to impaired learning abilities, paranoia and even a higher risk of schizophrenia.

How do drugs affect developing brains?

During this time when the brain is changing so fast, it’s especially malleable and more easily modified, making young people far more susceptible to addiction. The active ingredients in many drugs affect the brain like dopamine does, which is why drugs feel good to them. They get more pleasure out of drugs than adults do because they experience more intense highs. Studies with mice show that if they’re allowed to, adolescent mice will ingest two to three times the amount of alcohol, nicotine, and the active ingredients in other drugs as adults do—and yet they recover faster from the effects than adults. But repeated exposure to drugs sets up a need for more drugs in order to experience the same amount of pleasure. Most teens who experiment with cigarettes, alcohol and drugs do not become addicts. But you never know who will. We don’t yet understand the brain well enough to identify the genetics that make some people more vulnerable to addiction. We do know, however, that individuals who are exposed to these substances before age 14 are much more likely to develop problems than individuals who wait until age 21 or later. As one example, people who do not smoke as teens almost never become smokers as adults.

Given what we now know about adolescent brain development and the reality that many teens will take risks, what should we do to protect them?

We need a more comprehensive approach to supplement the educational programs already in place. Parents should constantly stress the dangers of driving while drinking. They should limit opportunities for their teens to get in trouble, from not allowing their daughter’s boyfriend to come over when they’re not home, to locking the liquor and medicine cabinets. Communities need to provide safe places where teens can gather. Law enforcement must enforce curfews and check for DWIs. Some states, like Pennsylvania where I live, have restrictive drivers’ licenses for teens that do not allow them to have other teens in the car until they have a certain amount of driving experience.

You had a recent opinion piece on CNN.com in which you advocated for raising the age to legally buy cigarettes to 21.

I feel strongly about this. Smoking is still the leading cause of death in this country. Even though anti-smoking education has been in place for many years, one in five high school seniors still smokes. In most states, you can legally buy cigarettes at age 18, so teens can either buy them or get them from friends. If we raise the legal age to 21, we will keep more cigarettes from younger teens who are far more vulnerable to the risk of becoming regular smokers. One estimate is that we could cut the number of high school students who smoke to less than ten percent in seven years simply by raising the minimum legal age to purchase tobacco.

Any suggestions for how drug resistance programs like Project ALERT can become even more effective?

Good programs are an important component in keeping our youth safe. Teens need the facts and they need to know how to resist temptation. Role playing, for example, can be a powerful teaching tool, one that educators can sometimes do more effectively than parents. I think part of this education should be giving teens more information about research on the brain. When I talk to teens, I explain exactly what you and I have been discussing here. They find it fascinating, and they really listen because it helps them understand why they feel the way they do and react the way they do. They respond to the science much more readily than to threats about getting cancer or emphysema in thirty years. It doesn’t work to try to raise them in a bubble. But sharing what we’re learning and keeping them up to date on the latest findings makes them our allies because they’re in on it. This is our best hope of helping them grow into healthy adults.

In your bestselling book, You and Your Adolescent, you recommend that adults adopt a zero tolerance approach to teen usage of cigarettes and alcohol. Yet you also advise that older teens be taught to use these substances responsibly. Isn’t that contradictory?

It’s realistic. The goal must be to get them to age 21 without becoming regular users because this greatly improves their odds of avoiding addiction. But alcohol and cigarettes are legal for young adults in our country. In my opinion, the best thing adults can do is to tell them that if they do drink or smoke, once they can do so legally, here’s how to stay safe, to not injure others, and to not become addicted. It’s the only realistic approach.

About Dr. Steinberg

About Dr. Steinberg

Laurence Steinberg, PhD, distinguished professor of psychology at Philadelphia’s Temple University, is a behavioral psychologist whose specialties include adolescent brain development, risk-taking and decision-making. In addition to his teaching, advocacy work, and research on the brain, he is the author, co-author, or editor of more than 300 essays and articles and ten books on teens. His most recent book is You and Your Adolescent: The Essential Guide for Ages 10-25, first published in 1997 and now newly revised. He is a regular contributor to the New York Times and National Public Radio.

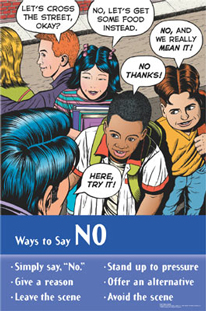

Now that the Project ALERT curriculum is available digitally, and is easily accessed free of charge from our website, we have leftover materials to share with you! The posters make great student giveaways, or display them in your classroom or hallways!

Now that the Project ALERT curriculum is available digitally, and is easily accessed free of charge from our website, we have leftover materials to share with you! The posters make great student giveaways, or display them in your classroom or hallways!